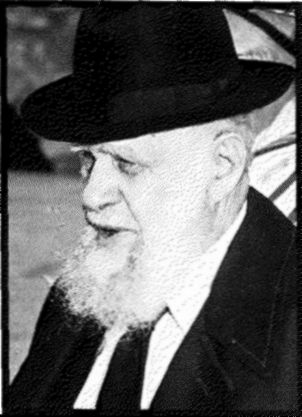

We are publishing this well-known story about HaRav Simcha Wassermann in honor of the shloshim, some thirty years ago.

"Well, bless my soul," thought Carolyn to herself when she opened the door. She had seen plenty of hippies in her time. Out in Santa Barbara, California, you could not escape them. These two young men looked weird, all right, no, different was the description, but she could not quite place them. The only thing that came spontaneously to her mind was that "Bless my soul". There was something pure and holy about them.

They stood there in their neat dark suits and hats, holding a funny metal box in their hand. They were far too young to be salesmen, and far too shy. She couldn't picture either of them sticking a foot in the door to command her attention. They were so unassertive. What could they be? What did they really want?

"Er, Mrs. Levine, we come from a new yeshiva in Los Angeles and we were wondering if you would be willing to take this pushke into your home."

Yeshiva? Pushke? Perplexed and outnumbered, she called to her husband, the successful young doctor, to come to her aid.

"Herbert, there are two nice young m... er boys here who want something."

Herbert came to the door. What clean-cut boys these were! He was impressed even before they said a word. And when he saw the charity box in their hand, it evoked a memory of his grandfather, who had religiously put coins in some old charity box before prayers each day. Grandfather was long gone, but the flavor of his Old World customs lingered on in Herbert, that is, Chaim's, memory with a faint but aching nostalgia.

"Is that a pushke you have?" he said, rolling the familiar word on his tongue. "Let me see it. Ah, so there is a Torah academy out in Los Angeles? Welcome to California. We could use some Judaism here; it's all but forgotten. Well, alright, I'll take your pushke. And good luck to you, fellas."

The boys thanked him politely and walked out of Dr. Levine's life. For the present. Their next stop was another likely candidate who might help support Rabbi Simcha Wassermann's new yeshiva.

What a disappointment that had been! R' Simcha had come to the west coast on the promise that his new yeshiva would have full financial support. But that had fallen through and now they were in trouble. In fact, it was said that the Rebbetzin had remained in Detroit so that she could support her husband on her salary. Aside from the major festivals, she did not join him for two whole years!

Herbert took the pushke. It felt funny in his hand. He had never felt an empty pushke. Even when the old Jew who had been his grandfather's friend had come periodically to empty it out, he had always replenished it with three coins, "Just to get you started," he would say, and they would settle down to a cup of tea and shmuess about old times.

"Alright then, here's a quarter to get you started," said Herbert with a nostalgic smile. He left the pushke on the mantelpiece and promptly forgot about it, because the next time he passed, it was no longer there. Carolyne had put the anachronism in the back of an odds-and-ends cupboard.

They had reason to recall the pushke about a year later when their seven-year-old Michael came of age. It was time to start him in school. The public school was out of the question and the Reform Temple school made both of them feel very uncomfortable.

"Listen, Carolyn, I still remember the real thing. My grandfather used to pray at an orthodox synagogue. This Temple is more like a church. It gives me the creeps. I don't want our son learning the nonsense they rake up from who knows where."

"I know what you mean. That organ and the ecumenical stuff is not for me, either. If anything, I want something more genuine. Our children should at least know something about their tradition. It is their heritage, after all. Whether they choose to practice or not is a different matter, but they should be exposed to the genuine thing."

"So we've agreed on it. What now? Where do we turn?"

Herbert was thoughtful for a moment, then snapped his fingers. "Hey, you remember that pushke that those two young kids brought a while back? Whatever happened to it? It had the name of some rabbi and a telephone number."

Carolyn went off to fetch it. There, in gold letters, was Rabbi Wassermann's name and phone number. His pulse quickening and throat dry, he dialed the Los Angeles number.

"A school for your boy?" said a firm but wise sounding voice at the other end. "Why sure! Why don't you come over and discuss it."

"I'll have to arrange for a babysitter. You see, my wife also wants to hear what you have to say."

"No need for that. Just hop into your car and bring the kids along," said Rabbi Wassermann, adding to himself, "A little good exposure wouldn't hurt them."

That was the turning point in the life of the Levines and of fourteen other families in Santa Barbara.

It didn't happen overnight, to be sure. Rabbi Wassermann did not operate like that. A big man in many ways, a giant in Torah stature, a man with a sharp, brilliant mind, he was very gentle when it came to his estranged brothers and sisters. More souls have been made at a Shabbos table than at a dialogue. And like his forerunner and Patriarch, Avrohom Ovinu, he preferred to work as a team, together with his wife and her famous gefilte fish and Yiddishe Mamma chicken soup. (She had by now joined him.)

There was one Shabbos after another, some jam sessions at odd hours and slowly, the Levines began assuming the responsibilities of mitzvos. At first, kashrus, then on to Shabbos and other important practices.

Six years passed and Michael was now a big boy, on the verge of his bar mitzva. The Levines respectfully insisted that their joy would not be complete unless the rosh yeshiva joined them for this momentous Shabbos. Having coached this family along for so many years, Rabbi Wassermann was confident that he could eat in their home and spend the Shabbos there, as well.

The couple showed up on Friday afternoon with their bags. The Levines beamed with pride and joy.

After exchanging commonplace pleasantries, R' Simcha spoke up, "And what's on the menu, this Shabbos?"

Menu? Didn't he trust them? Or was there something special that he craved? No, he wasn't gross like that.

"W-what do you mean? The traditional food. You know, gefilte fish, chopped liver, er... I don't know. What was it you wanted? Maybe we can still get it for the rosh yeshiva. A special wine? Everything is under the strictest orthodox supervision, just like you told us."

Rabbi Wassermann reassured them with a gentle pat on Herbert's arm and chuckled, "I just wanted to know if you had made some cholent."

"What was that? I-I don't think so. What is cholent, exactly?"

"Ah, cholent! I can tell you what it is, but that will be like describing a Rembrandt to a blind person. If you've never tasted it, you can't possibly know what it is."

"Is it too late to make some?" asked Carolyn apprehensively.

"Not at all. You take some beans, some potatoes, an onion and some good meat bones and throw them in a pot with water and seasoning. And out comes something indescribably delicious. A Shabbos treat. The Rebbetzin can coach you, I am sure. It won't be too much trouble to make me a small pot and keep it on the blech overnight, will it?"

"Anything to oblige. It is our deepest honor and we want this Shabbos to be perfect in every way."

The cholent was soon simmering on the fire. Before long, it began releasing characteristic odors that filled the house.

"Hey, Mrs. Herbert, what's that you got cooking on the stove?" asked Mary, their maid. "Smells great! You never made that dish before!"

"No, I didn't. The Rebbetzin made it."

The cholent simmered and bubbled all that evening, throughout the night and through the morning. Mary kept on wrinkling up her brow and sniffing. "That smell does something to me, you know? Deep inside. I can't put my finger on it. It seems very familiar."

When they went to wash their hands, Rabbi Wassermann couldn't help overhearing Mary's comment. Later, he tried to catch a few words with her.

"Mary, what is it about the cholent that stirs you up, so? Does it bring back any memories?"

"Yes, rabbi. Indeed it does. My grandmother used to make a dish like that just for herself and keep it on the fire overnight, just like Mrs. Levine did. Grampa wouldn't touch the stuff, though."

"Can you remember anything else about your grandmother, Mary?"

"Now that you mention it, she never called me Mary. She called me Miriam, but I didn't like it. It sounded too old fashioned. Not that Mary is much better, but it's much more common."

Probing gently into her past, R' Wassermann discovered that Miriam had a Jewish mother and a Jewish grandmother. In short, Miriam was Jewish, just like the Levines.

It did not take long to win Miriam over, as he had won over the Levines, the other Santa Barbrans, the hundreds of wayward Jews in France, in New York and now, in Los Angeles.

With their firm but gentle persistence, the Wassermanns became a byword in kiruv wherever they went, long before the word was popularly coined. Mary was just one point in case of their phenomenal success in this area.

The matter of the cholent simmered on the back burner in Carolyn's mind for a long time afterwards. Had Rabbi Wassermann known? Had it been prophetic foresight? Or just a lucky hunch? She could never really decide which...